Unlocking DNA Copyright Protection with Sequence Searches, Part 2

Unlocking DNA Copyright Protection with Sequence Searches, Part 2

Unlocking DNA Copyright Protection with Sequence Searches, Part 2

Aug 24, 2018

Aptean Staff Writer

Aptean Staff Writer

We welcome back guest blogger and thought leader Professor Chris Holman at the University of Missouri-Kansas City Law School for a new two part series. Professor Holman authors the well-known Holman’s Biotech IP Blog and is the executive editor of Biotechnology Law Report.

The first installment of this two-part series on copyright sequence searching focused on the Copyright Office’s use of search in conjunction with registration of engineered genetic sequences. The second installment addresses the sequence searching needs of synthetic biologists and others engaged in the development, use and/or commercialization of engineered DNA sequences.

Biotechnologists routinely conduct patent sequence searches in order to assess freedom-to-operate (“FTO”), or the patentability of a new product or service. If copyright is extended to engineered DNA, biotechnologists will for similar reasons likely perform analogous copyright sequence searches as a required element of due diligence. However, given the significant differences between the rights conferred by patents and copyright, the nature and objective of copyright searches will differ somewhat from those of patent sequence searches.

Defining the Parameters of Sequence Copyright

To a certain extent, the limited scope of copyright reduces the likelihood of inadvertent infringement. One of the most important distinctions between patent and copyright is that independent creation is an absolute defense to a charge of copyright infringement. By definition, a copyright is only infringed by “copying,” no matter how similar, or even identical, an accused work is to a previously copyrighted work. Furthermore, copyright should be limited to non-naturally-occurring, synthetic DNA sequences – under a DNA copyright regime any sequence of native origin will presumably be treated as part of the public domain and thus available for all to use. In principle, a synthetic biologist should not have to worry about copyright FTO, so long as her engineered genetic construct does not contain a sequence that has been copied from a previously copyrighted DNA sequence, e.g., her engineered sequence is based entirely on public domain, naturally-occurring DNA sequences.

But as synthetic biology advances, it becomes increasingly likely that newly engineered DNA sequences will be the product of modification and recombination of previously-engineered sequences. Under such circumstances, it will often be prudent, and at times imperative (depending upon the commercial potential of the engineered construct), for its developer to perform some sort of sequence search in order to clarify the copyright status of sequence elements introduced into the construct. While liability for copyright infringement requires copying, it does not require direct copying from the copyrighted work, nor does it require knowledge that the work was copyrighted. Unless a synthetic biologist knows the full pedigree of all genetic sequence information incorporated into a newly designed construct, extending all the way back to the original native DNA precursors, it will be impossible to know whether commercialization of the new construct could result in liability for copyright infringement.

How Publicly Available Sequences Increase the Potential for Infringement

This potential for infringement based on indirect and unknowing copying became an issue for the software community in the SCO/Linux controversy. Linux is a well-known “open source” software product, which users believed could be freely used and incorporated into new software products. However, beginning around 2003 a software company called SCO began filing lawsuits against companies such as IBM, essentially alleging that Linux includes code that infringes copyrights owned by SCO.

Significantly, the implication was that users of Linux, or even independently created software products incorporating elements of Linux, could be liable for unintentional and unanticipated copyright infringement. For a variety of technical reasons, SCO has apparently not prevailed in its lawsuits. Still, the case illustrates the danger of creating new, commercially significant copyrighted works based in part on previously developed works, even in cases in which the previously developed work is presumed to be in the public domain.

Similar scenarios could easily unfold in the context of engineered DNA. As engineered DNA becomes more complex, and further removed from naturally-occurring DNA sequences, it becomes more and more likely that synthetic biologists will incorporate previously engineered sequences into new works. The BioBricks Foundation, for example, has created a Registry of Standard Biological Parts. These “standard biological parts,” sometimes referred to as BioBricks, are functional units of DNA that encode for a specific biological function (like a promoter or protein-coding region). The Registry is intended to provide synthetic biologists with well-characterized, functional genetic sequences that can be modified and recombined to create new genetic constructs. The Registry espouses a philosophy of “Get, Give & Share,” and encourages synthetic biologists to donate sequences for inclusion in the Registry. But as illustrated by the SCO controversy, the incorporation of such parts into a new work could create the potential for copyright infringement liability unless the pedigree of the sequence is fully vetted.

Expanding a Market With Copyright Protection and Licensing

To be useful, it would be highly desirable that a copyright sequence search not only identify the presence of copyrighted DNA sequence elements, but also identify the owner of the copyright and its licensing status. If open source becomes an important component of synthetic biology, there could be a number of copyrighted DNA sequences that are made freely available to the user community. For example, a copyright owner could choose to make its DNA sequence available under a Creative Commons license, which can provide some blanket authorization for free use by the public. This authorization could apply to all uses, or as is often the case, could be limited to certain personal or academic uses, while requiring further permission for commercial use, including perhaps the payment of a royalty.

Even if a DNA sequence is not made available through some form of open source or Creative Commons-type of license, the copyright owner still might be interested in licensing the use of its copyrighted sequence commercially. In principle, a search to identify the owner of a copyrighted sequence might be conducted on a database provided by the Copyright Office. As a practical matter, to date, the Copyright Office has not provided very good capability for performing searches for registered works, but as noted in Part 1 of this series the Copyright Office could adopt the CPP suggestion to outsource the development and maintenance of a more user-friendly Registry of copyrighted DNA sequences to a third-party contractor such as GQ Life Sciences.

Optimally, such a Registry would be web-accessible, easily navigated and would provide accurate information as to the ownership status of registered sequences. The CPP White Paper suggests that copyright law should be modified to create greater incentives for registration, which would be a welcome development, since it would facilitate the creation of a more comprehensive and publicly-accessible database of copyright ownership information.

Private companies could also create searchable databases of copyrighted engineered sequences to facilitate rights clearance and licensing by third parties. There is precedent for such an approach. For example, Getty Images operates commercial databases that facilitate rights clearance in the context of photographs. A sequence search company like GQ Life Sciences from Aptean could provide a comparable database for engineered genetic sequences. If history is any guide, even if the Copyright Office does succeed in developing a searchable Registry of registered sequences, there will continue to be a market demand for a high-quality commercial alternative provided by the private sector.

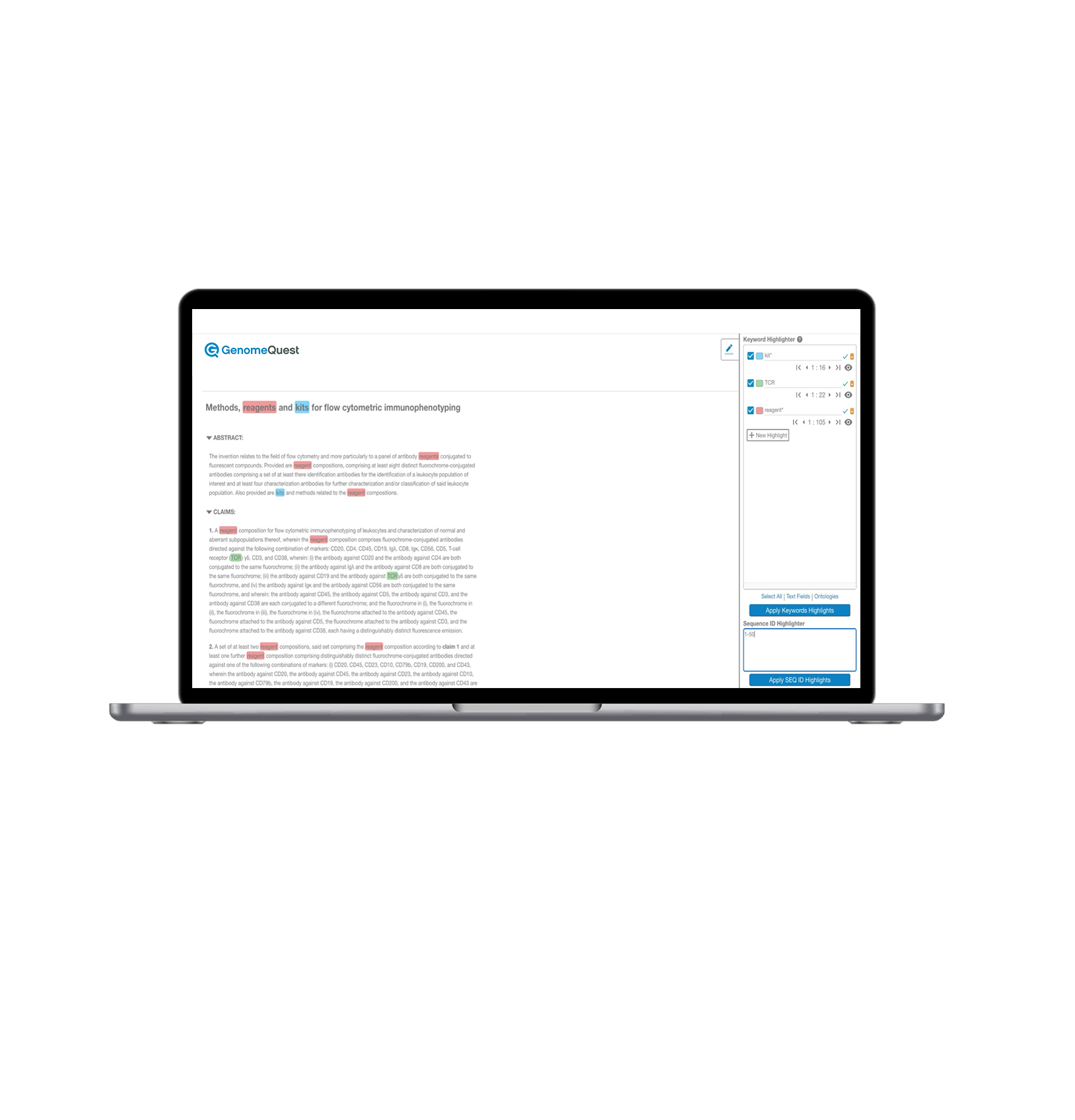

With its extensive data coverage (over 500 million sequences), powerful search tools and user-friendly functionality, Aptean GenomeQuest is the obvious choice for searching the entire sequence domain, both patent and non-patent.

Avoid the pitfalls of using free solutions for IP sequence searching. Download our RFP template or start a free trial today!

About Chris Holman

Chris Holman is a Professor at University of Missouri-Kansas City Law School, as well as the author Holman’s Biotech IP Blog and Executive Editor of Biotechnology Law Report. GQ Life Sciences is thrilled to have him be a guest blogger.

Ready for Your IP Sequence Search Solution

Use our free request for proposal (RFP) template to identify the right IP sequence search solution for your business.